Thursday, December 22, 2011

Friday, December 16, 2011

The long run finding is not surprising - to find otherwise would imply that (simply by reversing austerity measures) we could get 'money for nothing'. It is the short run finding that is both interesting and important - because it places importance on the pace with which austerity measures are applied. Few (if any) serious commentators would argue with the need to narrow the budget deficit. The choices are about how best to achieve this.

Monday, December 05, 2011

The leaders must tread a tough line - going too far too fast threatens democracy, but not going far enough threatens to prolong the crisis. A key part of the solution should surely involve automatic imposition of disciplinary measures. Conditional bonds continue to look as though they offer an attractive (albeit maybe only partial) solution.

Thursday, December 01, 2011

Meanwhile, the corresponding spread for Italy is proving to be somewhat more stubborn, though it has fallen by more than 0.75% points since 9 November.

Concerted action by several central banks, aimed at increasing liquidity by making it cheaper to borrow dollars, has been well received by the markets - possibly less for itself than because it hints at a growing awareness that the European Central Bank will indeed need to intervene through quantitative easing.

Monday, November 28, 2011

The OECD also expects (p.222) the output gap - the gap between actual and potential output - to rise during 2012; this is a predictable consequence of recession. In the wake of the severe fall in output during the Great Recession, their estimates of the magnitude of this gap still look to be on the low side.

The forecasts for unemployment, unsurprisingly given renewed recession and very feeble recovery, are for continued increases over the next two years.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Meanwhile, the Office for Budgetary Responsibility looks set to reduce its growth forecasts. This is no surprise - as I have stated elsewhere on this blog, a reasonable forecast for the coming months is for renewed recession. The credit easing package will not prevent this - the buffeting that demand is taking from the downturn in our major trading partners is too severe to be fully mitigated by any plausible dometic policy - but it will, to some extent, help.

Friday, November 25, 2011

Whether conditional bonds alone provide a solution to the current crisis is moot, however. The high interest rate premia (over and above German rates) that attach to Italian bonds - the spread is still around 5 percentage points. The corresponding measure for Spain is almost as high. The measures for Greece and Portugal are in silly territory. One might argue that the European Central Bank (ECB) needs to inflate some of the debt away in order to make conditions right for the introduction of conditional bonds. But if, by putting such bonds in place, we could guarantee that such an inflation would be a one-shot event, convincing the (still inflation-shy) German government that this is what the ECB must do might become a more feasible proposition.

Wim Boonstra (1991). The EMU and national autonomy on budget issues: an alternative to the Delors and free market approaches Finance and the international economy: the AMEX Bank Review prize essays, 4

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Monday, November 14, 2011

I first reported the dip expected for the last quarter of 2011 on this blog as long ago as June 2010.

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

One bank's reluctance to lend to another reflects a lack of confidence by the former bank in the latter - and across the system it suggests that bankers are becoming increasingly cautious. This has an adverse effect on the real economy as businesses and households find it harder to gain access to loans. At a time when growth is faltering, a second petrification of the financial sector represents really bad news.

And, as an article in last Tuesday's Wall Street Journal argues, the gap between base rates and LIBOR is now probably understating the extent to which financing has become difficult.

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

But the outlook for the current quarter and the immediate future remains challenging. World demand remains muted, and the fiscal policy stance within the UK does little to promote growth. On the monetary side, interest rates remain low and the quantitative easing programme has restarted - these policies have moderated the adverse impact of other things, but it is not clear that they alone will be sufficient to underpin continued growth over the coming months.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer will make his autumn statement on 29 November. This may need to offer some fiscal easing if the relatively good outcome of the third quarter is to be sustained.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Thirlwall, A. (1980). Regional problems are “balance-of-payments” problems Regional Studies, 14 (5), 419-425 DOI: 10.1080/09595238000185371

a 50% write-down for Greek debt held by private banks

additional finance for the Greek bailout package

the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) is to be extended

the EFSF will operate so that 'risk insurance would be offered to private investors as an option when buying bonds in the primary market' - in other words as an insurance

strengthening of the Stability and Growth Pact

changes in governance

The wording of the document is interesting. The 50% haircut is described as an invitation to 'Greece, private investors and all parties concerned to develop a voluntary bond exchange with a nominal discount of 50% on notional Greek debt held by private investors'. The additional financing for the bailout fund is intended to come partly from parties (such as the International Monetary Fund) which have not been party to these negotiations. The first question that needs to be asked about this agreement - the prerequisite for going past first base - therefore, is: will key parties that are being asked to fund this agreement agree to do so?

The proposals surrounding the EFSF are central to the agreement. As BBC broadcaster Evan Davis has tweeted: 'Don't you go to jail for selling insurance when you have no means of paying out?' One might add that premia rise with risk, and when the risk is high the premia could lie outside the reach of even the expanded EFSF. An alternative to leveraging the EFSF in this way would have been to free up the European Central Bank (ECB) as proposed by Charles Wyplosz and Paul de Grauwe. While some observers may be wary of the inflationary implications of quantitative easing by the ECB, inflation is simply not a threat at present. The ECB alone has the capacity to provide all of the funding that the EFSF could conceivably require. The agreement comes up short in this area.

The strengthening of the Stability and Growth Pact - intended to provide fiscal discipline - is a step towards fiscal union, but is likewise timid. After all, the Pact in its original form has failed rather spectacularly. The new agreement issues an 'invitation to national parliaments to take into account recommendations adopted at the EU level on the conduct of economic and budgetary policies'. The EU Commission and Council 'will be enabled to examine national draft budgets and adopt an opinion on them'. The language is a fudge, and past form suggests that it will be treated as a fudge. Likewise, the agreement states that 'national budgets should be based on independent growth forecasts' - and so they should.

The governance of the Euro area also receives much attention in the agreement. There will be regular summit meetings of the 17 member states that have adopted the Euro, these being chaired by a President of the Euro summit. Clearly this forms an inner core of 17 of the 27 EU members, the remaining 10 states being in a periphery. The future political evolution of a two-tier EU will be interesting.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

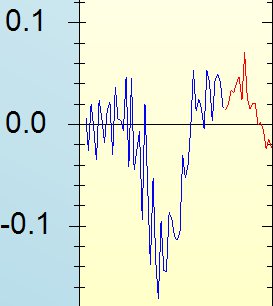

Using a similar method for the economy as a whole presents some interesting results. A google trends analysis of 'recession', confining the search to the UK, yields the time series shown in the graph below. This clearly indicates that searches rose in the run-up to the 2008 recession. There is some sign that it is rising again now - though the series is not clear on this, and data from the next few months could see the series go either way. (It is, perhaps, surprising that 'recession' is not trending more strongly given current fears about the state of the economy. Maybe people found out what they needed to know during the last recession, or maybe they are searching for other, related, terms now.)

Language is important. During the 2008 recession, 'credit crunch' trended (see the first graph below), but 'debt crisis' (the second graph) did not. Now the reverse is the case. The terms in which the popular media describe events presumably influence the terms for which people search.

Friday, October 21, 2011

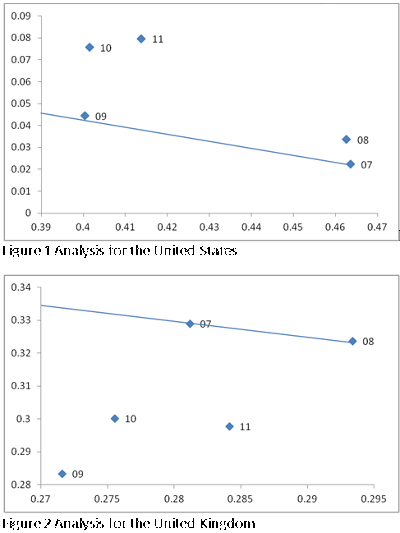

The lines represent the marginal productivity schedules, calculated using Mulligan's method, as observed in 2007. In the US, it appears that the shake-out of labour has not been associated with a fall in productivity. Indeed between 2007 and 2009 there was little change in the position of the marginal productivity schedule. Mulligan interprets this as indicating that the fall in employment over this period was due either to supply side shifts or labour market distortions, rather than to changes in demand. An alternative interpretation is that the impact of the recession fell disproportionately on low productivity workers. In the UK, by way of contrast, the observation for 2009 lies way below the marginal productivity schedule in 2007 and 2008. This may reflect a shake-out of high productivity workers, but it is arguably more likely to reflect the severe drop in demand suffered by the UK economy at this time. In both countries there appears to have been an upward shift in 2010-11 as their economies (temporarily perhaps) recovered.

While the marginal productivity schedule is, by now, higher in the US than it was before the recession, in the UK the schedule still lies well below the pre-recession position. In this country, at least, demand deficiency has been a key factor throughout the last few years - and it remains a problem.

Friday, October 07, 2011

The Bank of England has now announced a new wave of quantitative easing, amounting to a further £75 billion. This is in response to the alarming signs of slowdown in the economy. The announcement is welcome. It is also likely that the Treasury will start to purchase private sector assets as a means of improving the flow of funds, especially to small firms. Since this would represent an investment, it can be done outside the government's self-imposed fiscal limits. This too is welcome - if the free market in financial services is shackled, then such measures would appear to be necessary. The government may not be good at picking winners, but neither is a rapidly re-ossifying financial sector.

Could this expansion prove to be inflationary? There are very few signs that it could. The economy is still a long long way from capacity, and the effect on headline inflation of last year's VAT rise will soon vanish from the figures. Inflation should be the thing of least concern to policy makers at this time.

Monday, September 26, 2011

- preponing long-term investment projects

- to reintroduce the bank bonus tax in order to generate funds with which to support house construction and job guarantees

- a temporary suspension of employer contributions to national insurance for small firms that take on new workers.

- reducing VAT for a fixed period

- reducing VAT further for home maintenance and improvement

There is a mix of good and bad in these proposals. The first is needed, and is in any event in line with what some members of the government favour. The first half of the second bullet point deserves consideration as a means of raising funds; the second part is more suspect - why should the government be better at investing than the private sector? The proposal to cut national insurance has merit, though the requirement that it should be done for firms that take on extra workers might be hard to implement.

Then we come to VAT cuts. A temporary cut in VAT was introduced by the last government as a means of stimulating the economy. It is probably a costly way of having a limited impact. The last government did it because it was constrained by the political fall-out from its decision to scrap the 10 per cent rate of income tax. The present government is bound by no such constraints. If there are to be reductions in tax, they should take the form, not of a VAT cut, but of a hike in personal income tax allowances. That would put more income into the hands of the people most likely to spend it - and so it would likely be much more effective in stimulating the economy.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

In the UK, we have seen this reluctance reflected in the recent rise of the LIBOR - currently at 0.92, up from 0.85 a month ago. (It was 0.76 at the start of the year.) The banking system seems once more to be at risk of ossifying. At the root of this is the sovreign debt crisis in some European countries - while the possibility that Greece (in particular) might default on its public debt remains, banks that have lent to Greece are vulnerable, and other banks will not lend to them.

The fundamental problem is persistently put off rather than tackled. The extra loans will help, but only for the time being. One of two end points now looks inevitable. Greece defaults, or its problems are absorbed within a monetary, fiscal and political union of European states. Neither is particularly palatable. But it is time to stop kicking the can a little further on down the road and hoping that the underlying problems will go away (or come on someone else's watch).

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

"This is about economics, not ideology, not stubbornness. And our plan doesn't put a straitjacket on policy ... Deficit reduction was only ever intended as a means to an end ... Our troubles have very much been a demand crisis. The banks’ sudden withdrawal of funds, asset price falls, volatility in the markets – all hit demand. And even if we had the least regulated, most skilled, most competitive economy on the planet, if no-one spends any money, that’s not enough. Clearly, with debt so high – private and public – we have to be realistic about the restraints on boosting demand ... Investment in infrastructure stimulates demand not overnight, but more quickly than many supply side measures. And it raises productivity well into the future too ... If you modernise this kind of infrastructure you stimulate activity in the shorter term and you build systems high growth industries can use for years to come ... Last year the Coalition produced the UK’s first ever National Infrastructure Plan to deliver the world-beating infrastructure our businesses need from High Speed Rail, to Cross Rail, to green energy, to the best superfast broadband network in Europe. And we’re galvanising around that plan with renewed energy. A gear shift in government to unblock the system and get the money out the door ... We’re drawing up new money-raising powers for councils to do that where they can borrow against future growth from locally raised business rates ... We’re going through the nation’s capital spending plans to hand-pick up to 40 of the biggest infrastructure projects, the ones most important to growth, which will be given new special priority status. Each will be rigorously examined by Ministers to make sure there are no delays, no blockages and the economy feels the benefits as quickly as possible. That includes, for example, high speed broadband rollout, work to transform the efficiency of the national grid, major improvements to the rail network, like Crossrail and Great Western Electrification and projects to reduce congestion on our road network."

This is certainly a change in rhetoric. It sounds as though it might also herald a change in the phasing of the government's budget deficit reduction plan - about which we may hear more in the autumn statement on 29 November.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Some representatives of the banks have argued vociferously against the proposed reforms. Since the proposals serve to limit their degrees of freedom, this is not surprising. They argue that the proposals will lead to an increase in their costs - which they would pass on to their customers thereby jeopardising the economic recovery. The extent to which the banks could shift the burden of the new legislation onto their customers in this way depends on the extent of competition within the sector. The Commission's proposals for enhancing competition therefore deserve somewhat more comment than they have thus far received in the media. These are that mechanisms should be devised to make it easier for consumers to switch between banking accounts (through automatic transfer of information about direct debits etc.) and that the newly created Financial Conduct Authority should adopt a pro-competition stance. The Commission also notes that the divestitures currently planned and ongoing, respectively, in the Lloyds Banking Group and the Royal Bank of Scotland should serve to promote competition. These proposals are somewhat anaemic - where they go beyond a commentary on what is already going on they are vague - and they may need strengthening as they pass through the legislative process.

Subject to that caveat, there is much to commend about the Banking Commission's report. It should be welcomed.

Monday, September 05, 2011

The Chancellor claims that he has no Plan B; but Plan A can of course be morphed. As the economic outlook becomes increasingly worrying, and as the clamour for change increases, expect to see policy adjust sooner rather than later.

Friday, August 05, 2011

Default is an emotive term. There are many ways in which a debt can fail to be repaid in full - complete default is at one extreme, but there are other measures such as restructuring, partial repayment, and abnormal levels of inflation that can be used to reduce the scale of the liability. It is now inevitable that a significant number of economies in Europe (at least - let's keep America out of the discussion for now) will, in some form or another, default.

The easy money that has flowed in from the rapidly developing economies will no longer be so easy - investors in these emerging economies will have diminished confidence in the developed economies. In the medium term, it will become harder for the developing economies to live with debt. This further limits the wiggle room that governments in these economies have to manage the transition to a more stable path. We're in for some turbulent, and pretty horrible, times.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

One reason for the perverse figures observed in the recent past may be the very severity of the recession: real wages fell in 2009, and this may have enabled firms to retain workers that would otherwise have been shed, despite stagnation in output. With price inflation continuing at above 4 per cent over the year, there is still a lot of downward pressure on real wages.

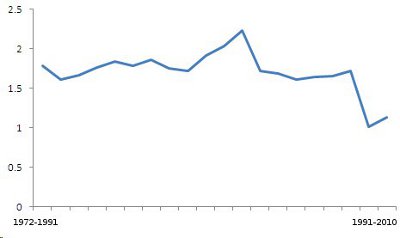

This suggests that the simple relationship between changes in unemployment and the rate of output growth which underpins Okun's analysis is misspecified - consideration also needs to be taken of movements in wages. In this respect, the true relationship may be closer to what Tom Hyclak and I once dubbed the 'Fisher curve' - in honour of Irving Fisher's work in the 1920s.

Over the long run, technological progress determines change in productivity. The decline in productivity will be temporary and we will see a return to growth in both productivity and real wages. When this happens, we can expect the Okun relationship to be restored.

Johnes, G. and T.J. Hyclak (1995). The determinants of real wage flexibility Labour Economics, 2 (2), 175-185 DOI: 10.1016/0927-5371(95)80052-Y

Monday, July 11, 2011

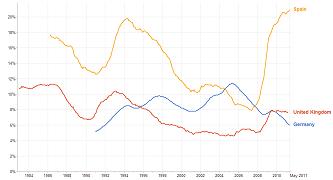

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, it is clear that unemployment has fallen in Germany while it has risen in the other countries - most severely so in Spain.

An interesting explanation for the relative success of Germany comes in a recent paper by Michael Burda and Jennifer Hunt. They argue that working time accounts - which allow employers to avoid paying overtime by averaging individuals' hours worked over a relatively lengthy period - have resulted in less hiring during the upturn and less firing in the downturn. This interesting finding suggests that such accounts are an institution that might be worth introducing elsewhere.

Thursday, June 23, 2011

It is not clear why, and it is certainly not clear that this drop represents a permanent shift.

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Recent data to emerge from the UK suggest that this law is being repealed. Output has been flat in recent months, but unemployment (far from rising, as Okun's law would predict) has been falling. In some respects this is easy to explain: workers are accepting wage settlements that are below inflation, so that the brunt of adjustment appears in the form of falling real wages rather than rising unemployment. Several factors may account for this: communication about the extent of the global readjustments required may have given workers a hefty reality dose; the union legislation of the 1980s, now really being tested for the first time, may have proven itself to be effective.

Increased union militancy challenges this last possible explanation. And however strong the reality dose might be, it is more likely than not that at some point resistance to real wage cuts will strengthen. Okun's law has been one of the more durable statistical regularities in economics over the years, and growth remains the most promising way of avoiding large increases in unemployment.

This forecaster has, for many months now, consistently predicted a dip in economic activity towards the end of this summer. Like any economic forecasts - indeed more so than most, given its simple nature - it comes with a 'health warning'. While some economic indicators - most recently the drop in the unemployment rate - provide welcome news, there is still some way to go before we can be confident that growth has been restored.

Monday, June 06, 2011

As early as May of last year, there were signs that the government intended to be flexible in the way in which it implemented the fiscal retrenchment. The Chancellor of the Exchequer has made much of the idea that there is no plan B, But the rhetoric is now changing - a plan B seems to be embedded within a plan A that is more permissive than the government's own rhetoric has often implied. For the sake of those who bear the brunt of this ever-so-slow recovery, let's hope so.

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

All of the models referred to above are designed to build up a story of macroeconomic behaviour using a strong set of microeconomic foundations. They are based on individual economic agents that are acting rationally. By drilling right down to the preferences of agents, the macroeconomic behaviour of the models is supposed to finesse the problem raised by the Lucas critique - the notion that, since a change in policy might change the way in which people respond to policy, models based on these responses cannot be used as forecasting tools. (But since people's preferences don't change in response to policy - only their behaviour does - models built on what we know about people's preferences are deemed to be robust.) In consequence, DSGE models have attracted much interest amongst central bankers.

But DSGE models are difficult to work with. Studying individual decision making in a dynamic environment - where attention has to be given to the way in which people form, and respond to, expectations about the future as well as how they respond to the past - involves a lot of complicated analysis. Simplifications have to be made. This being so, early DSGE models have focused on output and prices. While results from some of the models have been encouraging, many economists - myself included - have been underwhelmed by the general approach. This is because the models have failed to consider a world in which some people are unemployed. In other words, they have failed to consider anything that looks, even remotely, like the real world.

All that is set to change. Jordi Galí, one of the pioneers of new Keynesian DSGE models, has recently published work that accommodates the existence of unemployment. This has been built upon in further work done in collaboration with Frank Smets and Rafael Wouters. It's still early days, but the promise of DSGE modelling looks as though it may well be realised.

Galí, J. (2011). THE RETURN OF THE WAGE PHILLIPS CURVE Journal of the European Economic Association DOI: 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01023.x

Kydland, F., & Prescott, E. (1982). Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations Econometrica, 50 (6) DOI: 10.2307/1913386

Lucas Jr, R. (1976). Econometric policy evaluation: A critique Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 1, 19-46 DOI: 10.1016/S0167-2231(76)80003-6

Woodford, M., & WALSH, C. (2005). INTEREST AND PRICES: FOUNDATIONS OF A THEORY OF MONETARY POLICY Macroeconomic Dynamics, 9 (03) DOI: 10.1017/S1365100505040253

Thursday, May 19, 2011

In this example, the direction of causality can be inferred by examining the relative performance of students studying with different supervisors in the same doctoral programme, and by examining the relative performance of students who share the same supervisor where the supervisor works in more than one programme (usually in different institutions).

The results suggest that success is due more to the individuals' innate abilities than to the supervisors. Good supervisors tend to attract good students, but the early career publishing performance of a given supervisor's students is higher in doctoral programmes with a higher quality (that is, in programmes which likely attract more able students).

For universities, therefore, getting the programme right - attracting the right students - is a clear prerequisite for success. Understanding which comes first - chicken or egg - is crucial.

More broadly, the chicken and egg question is key to understanding a wide range of policy issues. Which causes which: class size or scholastic performance? risky behaviours of depression? investment or output?

Hilmer, M., & Hilmer, C. (2011). Is it Where You Go or Who You Know? On the Relationship between Students, Ph.D. Program Quality, Dissertation Advisor Prominence, and Early Career Publishing Success Economics of Education Review DOI: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.04.013

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

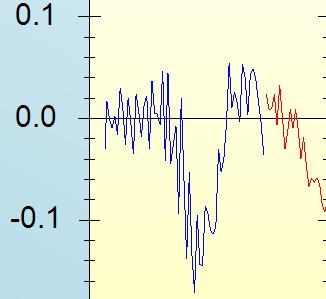

The caveats surrounding this model are many: it's based on industrial production data (since this is available monthly), and doesn't include information about other variables - notably policy. But for a simple model it has a rather good track record. While the pessimism in the model's forecasts may not be widely shared, these figures do serve to emphasise just how fragile is the recovery.

The graph below shows the actual data back to just before the downturn - the forecasts are at the right of the graph (where the line turns red) and look forward 18 months.

That said, from this low base, there are now some signs that offer encouragement. It remains essential for the government, in its zeal to attack the budget deficit, to pay heed to the impact that its policies has on growth.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

One would hope so. But the improvement in these statistics is slight, and in each case the data follow on from very bad figures in the previous month. If indeed we are seeing the first indications of recovery, that recovery remains very fragile. Whatever one's views might be about the speed with which the budget deficit is being cut, the policy shock that still has to be played out is likely to result in a bumpy ride over the coming months.

Wednesday, April 06, 2011

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

The Chancellor of the Exchequer described his Budget as a Budget to fuel growth, but beneath the hype there does not appear to be much fuel in the tank. To some extent this is unsurprising as the Chancellor has already used the Comprehensive Spending Review to tie his own hands. Even so, further - and more accelerated - redistribution towards those on lower incomes would have done at least something to improve the multiplier effect of what measures are in place to support the economy. The £600 rise in the personal allowance on income taxation does not kick in until April of next year - too little and too late to help an economy that is shrinking now. And a shrinking economy makes it all the more difficult for the government to meet its targets with the public finances.

The Budget has been accompanied by something called a 'Plan for Growth'. This aims to increase the competitiveness of the tax system, to encourage the creation and development of businesses, to rebalance the economy through investment and export activity, and to provide a more educated workforce. The headline ambitions suggest that the government's aim is to produce a raft of microeconomic policies that could help improve competitiveness and hence provide the right context within which economic growth can take place. So far, so worthy.

When we turn to the detail of the Plan for Growth, remarkably little involves a financial commitment by the government. There is reference to an additional £100 million to repair potholes, and one or two other things. But the (uncosted) words 'encourage', 'support', and references to reducing 'burdens' occur frequently. In other words, it's a 'do it yourself' plan for growth - much as the expenditure cuts were a 'do it yourself' exercise (a huge proportion of these cuts being shifted onto local authorities). The plan - inasmuch as it is a plan rather than a hope - is for a Thatcherian resurgence in enterpreneurship. We should wish for this to be successful. Whether or not it will be so will depend in large measure on the detail of the microeconomic policies that are introduced. And for that, we'll have to wait and see.

Monday, March 21, 2011

Ultimately the Liberal Democrats want to raise the personal allowance to £10000. While their more hawkish partners in government are unlikely to want to go the whole hog at this stage, it is, of course, now that the stimulus is most needed. Tax revenues fall when the economy contracts, and - while borrowing fell over most of last year while the economy was starting to recover - the more recent stagnation is doing nothing to help the public finances. Moving most of the way to the £10000 target - in a budget containing other policies to encourage growth - would be prudent.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Next week's budget needs to provide what has heretofore been lacking - not just a hope, not just a promise, but robust government support for growth. And if that means trimming the ambition just a little, and losing face just a little, then so be it.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

His nine points are:

1. In the wake of the crisis, policy making has to change, in particular with less of a focus on a single policy goal.

2. The pendulum has swung, some at least, in the direction of a recognition of an enhanced role for the state in macroeconomic regulation.

3. We previously underestimated the impact on the macroeconomy of microeconomic distortions.

4. There exists a multiplicity of macroeconomic policy tools...

5. .... not all of which are fully understood.

6. Some of these tools are difficult to employ for reasons of political economy.

7. The future research agenda for macroeconomics, with solid microfoundations, is exciting.

8. There should exist a multiplicity of policy goals. But moving from a model of inflation targeting to one where multiple goals are targeted is difficult.

9. We should not hope for too much.

In recent work, Georg Weizsäcker has produced compelling evidence that - contrary to much of the economic orthodoxy of the last 40 years - people do not form their expectations rationally. It takes particularly strong evidence to disturb someone's expectation away from their prior beliefs. If the expectations formed by an agent are approximately correct, they will not adjust them rationally. Only if they are way out will they take new evidence on board.

Weizsäcker's findings should not be particularly surprising. They suggest that a way forward in modelling may be to adopt a nonlinear approach wherein the degree of rationality used in forming expectations varies inversely with the accuracy of those expectations. Given the evidence, it is clear that our models would benefit by admitting some sort of learning mechanism - something more refined than the assumption that we always achieve rationality.

Weizsäcker, G. (2010). Do We Follow Others when We Should? A Simple Test of Rational Expectations American Economic Review, 100 (5), 2340-2360 DOI: 10.1257/aer.100.5.2340

Wednesday, March 09, 2011

The results are instructive. Unsurprisingly, Iceland, Greece and Portugal are amongst the countries with very little headroom. Italy and Japan are also in this group. Spain and Ireland (surprisingly, perhaps), are somewhat better placed. The UK is (perhaps also surprisingly) in a relatively comfortable zone, keeping company with countries such as France and Germany.

Thursday, March 03, 2011

The world moves fast. Understanding Society is set to be a fantastic source of data for researchers, but when analysing data we should pick horses for courses. Understanding Society is simply not up to date enough to provide useful information about consumer sentiment now.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

The notion that, with high and rising unemployment, the output gap is low seems to be difficult to defend. There are, to be sure, reasons why prices are rising. Oil and food prices have risen internationally for reasons that have been well documented (here and elsewhere) and which are likely to be transient. Tax hikes have also contributed.

The economy shrank in the last quarter. Fiscal policy is imposing a squeeze which will inevitably increase the challenges faced in the labour market. To move too early to accompany this with a monetary squeeze - and to do so on the basis of price statistics that are probably blipping - would be dangerous. Yes, we need to keep an eye on inflation, but, no, the price increases we have seen up to this point do not suggest that inflation is a significant threat.

Wednesday, February 09, 2011

Lending will be monitored by the Bank of England which will provide regular reports - which presumably means naming and shaming banks that do not live up to their promises. Beyond this, it is not clear that Merlin has any teeth. Banks will lend, and they will do so at rates of interest that they themselves set. If businesses do not find these rates attractive, they will not look for loans.

In this context, it is a little disquieting to note the continued rise of LIBOR - which is now at 0.80%, some 30 points above the Bank of England's interest rate. There is still a lot of nervousness around the financial markets, and that means that lending is still not going to come cheap.

So the environment in which Merlin has been launched is not altogether promising. A little more prescription might not have gone amiss.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Occasionally over recent months, I have referred to a forecasting model that I like to use. If the slump in the last quarter of last year was indeed due to the exceptional weather, then this model should fail to predict it. Indeed my model fails to predict the final quarter slump. So snow may have played a part. (Bear in mind, though, that this is a loose test - not least because the data I use in this model are industrial production data, and we know that manufacturing did relatively well in the last quarter.)

Despite this, the model's forecasts are not all that encouraging. They are that production will show modest growth (at an annualised rate of less than 2%) up to the late summer - but then it starts to fall off.

Plenty of caveats attach to a simple model of this kind (a neural net with a hyperbolic tangent squasher, 24 months of input data, 2 hidden layers, where the data are the 12-month change in logged index of industrial production data), or indeed to any economic forecast. But, for a simple model, the track record of this forecaster is pretty good. Snow may have played its part in the last quarter of 2010, but the recovery is nonetheless far from secured.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

The figures are considerably worse than the expected increase in output of around 0.4%. It represents a dreadfully weak platform on which to build the government's austerity measures. It is time for a reassessment.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Economics is often thought of as the 'dismal science' - when there is good news about unemployment, there is usually some bad news about inflation, and vice versa. When there is bad news about both, things get really dismal, and we really have to try hard to look for some good news. There may be some. Petrol prices have risen sharply; food prices have also increased. The price of oil does tend to fluctuate a lot (a fact not unrelated to the inelastic nature of both demand and supply in this market), and at close to $100 per barrel the price is now, if anything, above its steady state. The increase in the price of food has been driven largely by severe, but transient, weather events.

So where is the good news? As things stand, it looks as though inflation is blipping. It will rise further before falling - not least because of the effects of the January VAT increase. But as oil and food prices stabilise, the inflationary pressure should ease.

This does suppose that the inflation that we have experienced up to now will not feed through into wage increases. If it does, then stagflation indeed looms. The Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee is sure to look closely at wage settlements over the coming months. If there were to be a general upward drift in wage settlements, then that would not be good news for inflation - wage hikes would feed through into further price hikes, and this would lead to wages and prices leapfrogging each other in an inflationary spiral. To avoid this, the Bank may need to raise the interest rate sooner rather than later - and that would further threaten the recovery. Let us hope that sense prevails.