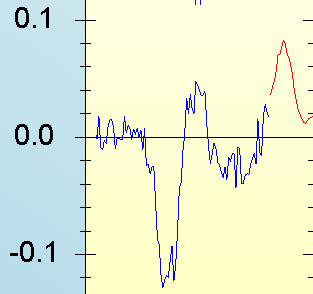

Economic forecasters have received a rough ride in the media, often for good reason. The Great Recession was not well predicted by many economists - though there are some notable exceptions. In general GDP growth was overestimated both at the onset of the recession and over subsequent years - only more recently, in the UK, have the forecasts (very markedly) underestimated the extent of growth.

The OECD has produced an evaluation of their own forecasts over this period. Two findings are of particular note. First, forecasts for economies that were particularly open to external shocks were relatively prone to large errors. The impact of contagion of the financial crisis was underestimated. The global interlinkage of financial markets is a feature of the microeconomy that macroeconomic models - even those (maybe particularly those) with strong microfoundations - were not particularly well equipped to handle. This implies that forecasters need to learn a lesson about this aspect of their models (and to some extent they have already done so).

Secondly, forecasts were unusually error prone in economies that, before the recession, had more rigid regulation in their product and labour markets. In such economies, rigidities generate more extreme variations in employment and output than in economies where prices can bear the brunt of economic fluctuations. The modelling of such impediments to the free movement of prices calls for quite detailed understanding of institutional arrangments within the economies under study, and it is clear that this understanding needs to be improved if forecasters are to better their performance.

It should, however, be borne in mind that - while many observers like to judge economists on the basis of their forecasting ability - forecasting is far from the be all and end all of economics. Understanding the past and present is arguably more instructive (and - given the uncertainties that the future inevitably brings - more achievable) than accurately reading the statistical tea leaves.