Over the last year or so, I've been blogging mainly from the

Work Foundation site. This would seem to be an appropriate time to mirror these posts on this site, all in one go. Formatting will be untidy and links to source material won't appear as they did in the original (Work Foundation) posts, but if you see something interesting and want to know more I'm sure you'll be able to find your way via the Work Foundation site.

March Director's report

17 March 2015

Much of the recent media commentary on technological progress foments fear. Barely a week passes without a new story about robots stealing our jobs. These

scaremongering stories miss the point that the nature of the work that we do has always evolved over time - our jobs will not be stolen, but they will

inevitably morph. For sure, our education and HR development systems need to be fleet of foot in order to react to the changing needs of the labour market.

But we should remember that, where they are adopted, new technologies will, generally speaking, come to the fore because they improve things for us. After

all, technological developments are human constructions; we have a choice.

Indeed, far from being a threat, the problem with technology in recent years - in the UK at least - has been that it has advanced far too slowly.

Between 2006 and 2011, the number of UK patent applications fell by some 15%. Over the same period, business enterprise investment in research and

development rose 9% from £16.4 billion to £17.8 billion (in 2012 prices); this followed a 3% real increase over the preceeding 5 years. While patent

numbers are a crude guide to the value of innovation, these data suggest something of a decline in the returns to investment in R&D. There is, of

course, a long literature, including the work of Zvi Griliches, Bronwyn Hall and others, pointing to a long term fall in the return to investment in

R&D in the US, and more recent studies have addressed similar issues in the UK, albeit for the period before the Great Recession. For the period

since, some evidence comes from NESTA's innovation index- which sums the percentage changes in all forms of private intangible capital and total factor

productivity. After a long period of growth, this fell by 2.0% in 2008 and by 6.8% in 2009, and has barely been positive since.

Business investment more generally has been identified by some observers as a key factor explaining the sluggishness of productivity. This is indeed likely

to be an important factor; from its peak in the second quarter of 2008, real terms business investment fell by almost 20% over the course of seven

quarters, and a subsequent partial recovery stalled in 2012. In late 2013 and early 2014 it recovered again, at one point rising at an annual rate of more

than 10%. But business investment has slid back over the last couple of quarters. The median forecast for business investment growth in 2015 now stands at

5.6% - down from the 2014 figure of 8.1%.

Measures designed to provide a healthy framework in which investment, and particularly successful investment in R&D, is encouraged include the

strengthening of patent protection and fostering of product market competition. Ensuring that firms with strong capacity to innovate have access to finance

is key, and promoting this is likely to require new instruments and methods for evaluating companies' stocks of intangibles.

While the productivity puzzle remains a conundrum largely because there is in truth a plethora of underlying causes, ensuring that the policy framework is

one that encourages successful innovation is likely to reap a high dividend in this arena. It is reassuring to note that this has come to be high on the

political agenda. For the longer term, as well as for fixing the short term issue, this will need to be a priority for the next government.

A bit more evidence on pay below the Living Wage

23 February 2015

The TUC has released an instructive analysis of low pay by locality, based on data from the House of Commons Library. The findings suggest that in some

areas more than half of all employees are being paid less than the Living Wage. These areas range from urban centres such as Birmingham Northfield and

Enfield Southgate to rural areas including Dwyfor Meirionnydd. At the opposite end of the scale, the proportion of employees paid less than the Living Wage

is just a little over 10% in several parts of London, but also in Dundee West and Cardiff North.

The Living Wage is an interesting metric, not least because it provides a rough and ready guide to the extent to which workers need support from the

welfare system in order to make ends meet. If there is a high proportion of workers not earning enough to meet basic needs, demands on the welfare state

are likely to be considerable, and consequently government will experience difficulty in making significant reductions in its own expenditure and so in

tackling the budget deficit.

This is just a rough metric, though. In practice it matters who is earning low pay. It may be young people working part-time while still in full-time

education; it may be adult workers with families to care for; it may be one, or it may be both, earners in a two income family. Unfortunately the TUC data,

based as they are on data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), cannot provide much information about this.

Data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) can, though. It should be emphasised that these data are not as comprehensive as the ASHE data for the

consideration of earnings, but the LFS data nevertheless provide some useful additional information. I have used the most recent available four quarters of

data in the analysis that follows - from 2013Q4 through 2014Q3.

In all, some 27.1% of 16-64 year olds in the LFS data were paid below the Living Wage. This figure is somewhat higher than the ASHE equivalent. This may be

due to differences in sampling or in the way the data are collected, but it should not unduly affect the relativities reported below.

To some extent, there is a concentration of low pay in the youth labour market. If we restrict the sample to those aged 25 or more, the proportion of those

earning less than the Living Wage falls to 23.0%.

Gender differences are marked. Some 32.8% of female 16-64 year olds are paid below the Living Wage, but the corresponding proportion for men is just 20.9%.

If we look just at workers who are not currently married, some 34.8% are paid below the Living Wage. For men who are not currently married, the proportion

is 30.3%.

In many respects, the most interesting group is those who are married. It is important to know the extent to which individuals with low pay tend to have

spouses who also have low pay. The greater the extent, the greater are the implications for poverty and the greater the implications for the welfare

system. Some 19.0% of married respondents with earning partners earn less than the Living Wage. There is a marked gender differential, with the proportions

being 25.9% and 12.2% for married women and married men respectively. Some 5.9% of households with married earners have both partners earning less than the

Living Wage – a much lower proportion than is observed for other groups.

These statistics are instructive in providing greater detail on the demography of low pay. The concentration of low earnings amongst those not currently

married - and in particular amongst women - should be a matter of concern.

The economic recovery, in terms of employment gains, has been impressive so far. While there has been some evidence in recent months of wage increases,

there has also been some evidence that the gains have been skewed, with those in the lower part of the income distribution gaining relatively little. Low

pay is obviously a problem for those who do not receive sufficient earnings to meet their basic needs. But it is also a much wider problem that is

affecting our ability to pay back the deficit. Putting in place the conditions for a productivity revival - encouraging investment in physical and human

capital, stimulating demand - should be the priority for the labour market over the coming months and years.

Director's February report

18 February 2015

One of the major research themes at The Work Foundation in recent years has focused on the issue of youth employment. Three years ago, the numbers of young

people (aged under 25) who were unemployed exceeded a million. This was profoundly harmful to the young people directly affected, of course, and moreover

it represented a huge wasted resource for the country as a whole.

Since then, youth unemployment has fallen along with the overall unemployment rate. The latest data indicate that some 763000 young people are unemployed.

This amounts to an unemployment rate of 16.8%, well above the 5.8% rate that attaches to the labour force as a whole.

The latest set of data on underemployment produced by Bell and Blanchflower - and published on The Work Foundation's website earlier this month - further

highlight the difficulties faced by young workers. Not only are young workers more prone to unemployment than are their older counterparts, but they are

also more prone to underemployment.

Taking the labour market as a whole in the UK, underemployment only became a noticeable feature during the Great Recession. Until 2007, the underemployment

rate tracked the unemployment rate quite closely. But then a gap of around 2 percentage points opened up, and this has started to close only in recent

months. For young workers, however, underemployment has been a feature for much longer. In 2001, the earliest period for which data are available, the gap

between the unemployment rate and the underemployment rate for this group amounted to 4 percentage points. This opened up to more than 9 percentage points

in 2013, and even now remains as high as 7.5 percentage points. This means that, the underemployment rate for young people in the UK currently stands at

some 24%. This is a huge underutilisation of talent.

The Prime Minister has laudably promised to 'end youth unemployment' in the next parliament. The data suggest that such a promise, welcome as it is, does

not go far enough.

The Bell and Blanchflower data throw light also on the incidence of unemployment and underemployment by ethnicity. Taken as a whole, the figures paint an

uncomforatble picture for young people. The unemployment and underemployment rates faced by young people from ethnic minorities - and especially by young

black people - are huge. The unemployment rate for this group remains above 30%. Once account is taken of workers who wish to work longer hours to

calculate an underemployment rate, the figure rises to well over 40%.

Education has long been promoted as a route to a better labour market experience. It certainly helps. But alone it is insufficient to close the gaps noted

above. As we argued in our written evidence to the Education Select Committee last year, young people should be protected from adverse labour market

conditions, and this requires construction of a new framework for the delivery of employment, skills and welfare to work schemes.

The youth labour market is far from fixed. At The Work Foundation we shall continue to conduct research in this important area, informing advice that can

help transform policy to the benefit of (what, given the extent of underemployment, we still consider to be) the missing million.

Young, gifted with underemployment, and black

04 February 2015

The latest release of underemployment data in the Bell-Blanchflower series has highlighted sharp differentials by age and by ethnicity in workers’

experience in the labour market. These differentials are explored further in the table below, which draws on pooled data from the most recent available

four quarters of the Labour Force Survey The unemployment rate for young people – those who have left full-time education and are aged under 25 – varies

markedly across ethnic groups. For all groups, however, the rate is well above the corresponding rate for the overall population of working age. The

unemployment rate is particularly high for young black workers. To some extent young people can mitigate the harsh environment of the labour market by

investing more heavily in their own education. Rates of unemployment are lower – and in the case of young black workers markedly so – for those who leave

education beyond the age of 18 than for those who leave earlier.

As is made clear in the Bell-Blanchflower data, the young suffer disproportionately from underemployment, with many young workers wishing to work longer

hours than they currently work. This is captured, albeit crudely, in the table by the second row of data – which shows what the unemployment rate would be

if we counted as unemployed all those who work part-time. The incidence of part-time working across all groups of young workers is huge. Again, young black

workers appear to be the most disadvantaged group.

Education certainly helps young people make their way in the labour market. But the data reported here suggest that a wider range of solutions are called

for in order to alleviate the wasted resource represented by young people.

The latest underemployment statistics from Bell Blanchflower

04 February 2015

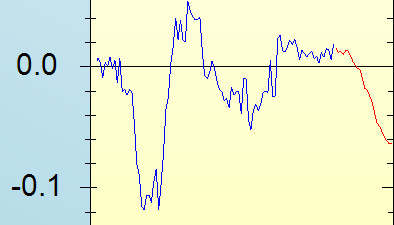

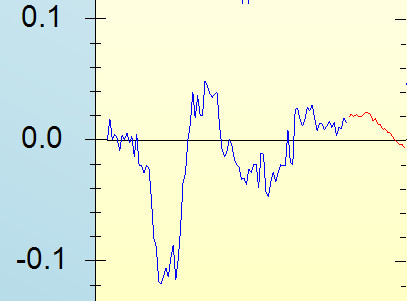

The latest figures on the Bell and Blanchflower underemployment series have now been produced and are reported below. The underemployment rate is

constructed by adding to the unemployment count a full-time equivalent of the net number of hours for which workers who are currently working fewer hours

than they would like to work are employed. Until 2008, the unemployment series and the underemployment series followed each other closely. Since then, the

rate of underemployment has been consistently above the rate of unemployment. This means that the unemployment rate is no longer a sufficient measure by

which to judge the extent of slack in the labour market.

The figures for the third quarter of 2014 show that, as unemployment has fallen, so too has the underemployment measure. While the gap between the two

rates amounted to more than 2 percentage points in the first quarter of 2013, it is now reduced to a little under 1.5 percentage points. This suggests that

the labour market is returning to normality - but slowly; the unutilised supply of labour is still markedly greater than the relatively low rate of

unemployment might suggest.

There are interesting differences by gender, age and ethnicity. While the unemployment rate is slightly lower for women than for men, the underemployment

rate for women is higher. This suggests that women are particularly likely to be working part-time when they would like to work longer hours.

Amongst young people, rates of unemployment are high - currently just above 15 per cent. But this group is particularly prone to underemployment - the

underemployment rate is almost 24 per cent. At the Work Foundation, we have often spoken of the 'missing million' young workers - with many working

part-time, it is no longer the case that a million young individuals are without work, but the full-time equivalent level of workkessness amongst this

group still amounts to well over a million. This resource has the potential to deliver huge output gains for the economy.

Rates of unemployment are particularly high for young people in ethnic minorities, and, amongst these, particularly so for black youths. There was,

however, a particularly marked fall in the unemployment rate for this group over the first three quarters of last year. But that fall has been accompanied

by only a very slight dip in underemployment. The good news that these workers are finding jobs has to be tempered by the fact that many of them are

looking to work longer hours.

Looking at ethnic minority workers across all age groups, both unemployment and underemployment rates are higher than for white workers. Indeed the

underemployment rate for black workers remains above 20 per cent - though the unemployment rate is a little under 15 per cent.

In sum, the new data provide some encouragement that the labour market is moving in the right direction. The gap between unemployment and underemployment

rates is getting smaller as the economy returns to health, but it is still substantial, and it would be rash to use the unemployment rate alone as a

measure of labour market tightness.

Director's January report

20 January 2015

At the start of a new year, we are all tempted to ask the question: what will the next 12 months bring? So let me try and answer this from the point of

view of a commentator on the labour market in the UK. It’s an easy question to answer in a single word – uncertainty.

That answer is, of course, more than a bit of a cop-out. So let me spell out three areas where this uncertainty is likely to manifest itself.

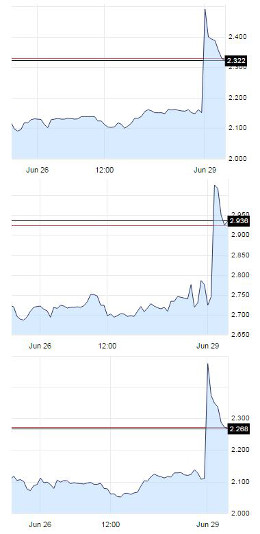

First, the strength of the economic recovery and the consequent impact on the labour market is likely to depend crucially on developments in our major

trading partners. The recovery in mainland Europe remains weak, and this has already started to put a brake on recovery in the UK. GDP growth in 2015 is

likely to be slower than it was in 2014. How much slower is unclear at this point, however. A major source of uncertainty surrounds the possibility of

Greece leaving the Eurozone – the so-called ‘Grexit’. This has become an issue once again in the run-up to the Greek election on 25 January. When the

possibility of a Grexit was mooted a couple of years ago, the fear of contagion and a subsequent wider collapse of the Eurozone was acute. With interest

rate spreads now being more moderate, such contagion is less likely, but the impact of a Grexit could nonetheless be considerable. This is particularly the

case if the exit were accompanied, or quickly followed, by Greece defaulting on debt. Several of our major trading partners would be exposed in this

scenario and their growth prospects – and hence ours too – would be compromised.

Secondly, the UK’s own election in May will be one in which the policy offerings of the major parties will have distinct labour market effects. The parties

have stated their ambitions for narrowing the budget deficit. In so doing, they make very different assumptions about the way in which these aspirations

will affect economic growth. Take your pick: but whichever set of assumptions you go along with, there will be uncertainty about how growth – and hence the

labour market – will evolve over the coming period while we still do not know the outcome of the election. Moreover, on at least one scenario, further

uncertainty is provided by the possibility of another ‘rexit’ – the ‘Brexit’ – with the possibility of a referendum on British membership of the EU. Once

again you can take your pick about the assumptions you make about the likely labour market costs and benefits of a Brexit – but until you know the outcome

of the election and any referendum, uncertainty will prevail.

Thirdly, there is uncertainty about whether growth in productivity will be restored. Business investment increased healthily over much of 2014, and

ordinarily we would expect to see this reflected in productivity gains. That improvement in investment needs to be consolidated in 2015, however – and the

uncertainties in the environment may not help in this regard.

Even if productivity recovers strongly in 2015, it is not clear that this will translate into a sustained increase in real wages. While simple models

equate wages with marginal product, simple models sometimes fail to capture pertinent information. US evidence suggests that the link between productivity

and wages has broken down. If that is a result of the twin forces of global trade and technological developments, then we can expect to see such a

breakdown in the UK too. Increased productivity may turn out to be a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for wage growth. It would be good news

indeed if the recent increase in real wages turned out to be sustainable – but whether or not it does still remains to be seen. It cannot simply be assumed

that pre-recession trends will be restored.

In light of all this uncertainty, decision makers in business and government need sound advice and regular updating. At The Work Foundation, we play our

role in this partly by disseminating our work through our newsletter. I hope you will find something useful here.

Rate of growth of weekly earnings now well above the rate of inflation

17 December 2014

The latest release of statistics on the labour market offer almost uniformly good news. Employment levels continued to rise, by 115,000, in the latest

quarter. Meanwhile unemployment fell by 63,000, with the headline rate of unemployment remaining at 6.0%.

The more detailed statistics suggest a continuing trend towards restoration of normality in the labour market. The number of employees in employment

increased by 165000, with a reduction of 29000 in self-employment. Amongst those who are self-employed, the number working part-time fell by 34000 while

the number working full-time rose slightly. Meanwhile the total number of people working full-time increased by 166000, and there was a reduction of 51000

in the number working part-time. This is all reassuring news. We have expressed concern in recent months about the high levels of insecurity that remain in

the labour market. While this is still a concern, the latest figures indicate that we are clearly moving in the right direction.

The employment gains have been particularly pronounced in the utilities, transport and storage, and arts and recreation. The sharpest quarter-on-quarter

change was in the North West, with an increase in employment of some 35000. This region has been performing exceptionally well of late; recent data on

gross value added for 2013 showed it to be (along with Wales) the fastest growing region at 3.4%. Meanwhile employment declined in the most recent quarter

in London and the South East – regions that have been seen as the engines of the recovery.

Arguably the most significant development this month has been the rise in the rate of growth of weekly earnings – up 1.8% on a year ago. This increase is

now well above the rate of price inflation. The increase has been particularly marked in finance and business services (3.0%), with earnings in the

construction industry also rising quickly (2.7%). The recovery in finance comes on the back of a steady increase over the last three months. In

manufacturing, however, the rate of growth of earnings has moderated somewhat, reflecting muted growth in the production sector.

Director's December Report

11 December 2014

The Chancellor’s Autumn Statement earlier this month set out plans for restoring budget balance by 2018-19. These are welcome not least because they have

stimulated debate across the political spectrum about how fast government should go in closing the deficit.

Economic policy both affects and responds to conditions in the broader environment. In 2007-08 public sector net borrowing amounted to only 2.7% of GDP. In

response to the recession it rose to 6.7% and then 10.2% in the following two years. Reversing this has proved to be difficult. After two years of

austerity, the rate at which inroads have been made into the deficit has slowed considerably. In many respects this was a good thing. The economy was

flatlining, and, with monetary policy already as relaxed as it could be, putting the brake on further fiscal tightening probably prevented a second

recession.

A good thing it may have been, but it was also largely accidental. Receipts from taxation have been lower than might have been expected at this stage in

the cycle, and government expenditures have been higher. The reason for this is that the recovery has taken on a peculiar form. Over a million more people

are in employment now than four years ago, and there are more than half a million fewer people unemployed. But the recovery has not been as remunerative

for the Treasury as has been the case in the past, with real wages falling for many years after the trough of the recession. With many new jobs paying

wages in the space between the national minimum wage and the Living Wage, tax receipts from the extra income have been limited, and the government has

needed to pay out additional in-work benefits.

The preponderance of jobs at this end of the wage distribution is due to many factors. The supply of labour is buoyed by the implications of ageing and the

abandonment of a default retirement age, and also by immigration. Global competition and technology both have adverse implications for the demand for

workers of intermediate skill, as witnessed by the ‘hollowing out’ of the labour market. The key issue, however, relates to the primary determinant of real

wages, namely productivity.

Productivity has stagnated in recent years. There are many reasons for this – and we have explored these in depth at the Work Foundation. There is,

however, nothing inevitable about the productivity puzzle. In the US, productivity continued to rise steadily through and beyond the recession years.

The predictions made in the Autumn Statement assume that productivity will rise, bringing about an increase in real wages and hence in consumer spending.

If these predictions turn out to be ill-founded, the target of closing the budget deficit within a few years will be unrealisable. That being the case, one

might have expected more focus in the Statement on how business investment can be supported in ways that enhance productivity.

But of course, enhancing productivity is something that is in businesses’ own interests too. As changes in the world around us redefine how various tasks

are undertaken, so businesses need to undergo a zero-based rethink of the ways in which jobs are configured. How can tomorrow’s jobs best be constructed,

from scratch if need be, so that they use workers’ skills to full effect, and provide workers with career structures, progression, and growth? If employers

could answer that question, they could enhance productivity in their own organisations, offer increased living standards for their workers… and solve the

government’s problems with the public finances.

Autumn Statement lacks a clear vision of the route ahead

03 December 2014

Today’s Autumn Statement tells us something about the way in which the government sees the economy moving over the next few years, and rather less about

how it plans further to reduce the budget deficit.

After peaking at 3% this year, GDP growth is expected to fall to 2.4% in 2015. That is no surprise – indeed I have been predicting a slowdown next year for

some time, and the sluggish performance of the UK’s major trading partners in recent months reinforces the view that broader economic conditions do not

offer a favourable wind. The longer term projections for growth are for it to stabilise at between 2.2 and 2.4 per cent each year to the end of the decade.

This probably has more to do with the structure of the econometric models used in forecasting – which tend to revert to a mean – than any serious

assessment of the economics. We might be so fortunate, but equally we might, post-recession, be in a new world in which the secular rate of growth is

slower than it was before.

The public finances are forecast to improve dramatically beyond the current year. Last year’s outturn was a deficit of £97.5 billion. This year’s is

expected to be slightly lower, at £91.3 billion (down from £133.9 in 2010-11). But by 2016-17 it is expected to be only £40.9 billion, and the following

year just £14.5 billion. In percentage terms – as a percentage of GDP, that is – the deficit is expected to be 5.0% in the current year compared with 8.4%

in 2010-11. It is coming down, but slowly. If the recent strength of the economy were to be maintained, there may be scope for tightening the belt – but

many indicators suggest that this year’s strong performance has been a blip, and the Prime Minister may well be right to suggest that ‘red warning lights

are once again flashing’ in the economies of some of our major partners. In any event, the Autumn Statement provides little information about how the

turnaround that is still sought in the public finances is to be achieved, not least because the changes in planned expenditures and revenues announced

today imply only a small net gain.

Big money changes include an increase in personal tax allowances, a major reform of stamp duty (moving to a marginal rate system), a restriction on tax

relief that banks can claim on losses made in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and new employer contribution rates for public sector pensions.

Moreover, a scheme will be introduced to tax multinational enterprises that seek to declare profits overseas rather than face UK tax; how this will be

implemented is unclear.

Certain items of specific public sector investment are worthy of note – the Sir Henry Royce Institute for advanced materials will attract £235m in

Manchester, and a Big Data centre at Daresbury will attract £113m. These are significant investments in the North West – though the Alan Turing Centre on

Big Data will be located in London (which some may see as perverse given his connection with Manchester). Further investment in the Northern Powerhouse

includes infrastructure improvement, including road improvements in Merseyside and on trans-Pennine routes, HS3, and investment in other rail services.

While the Chancellor announced several public investment projects, the Statement is disappointingly thin on measures to promote business investment. There

are minor changes to R&D credits, and proposals to extend the work of the British Business Bank, notably through an extra £400m under the

Enterprise Capital Funds programme.

On the labour market, there are proposals to extend the National Insurance break for firms employing young workers to cover all workers under the age of 25

on apprenticeship schemes. While it is good to see the importance of youth training acknowledged, it is not clear that this is the best way to achieve

progress in this area. The quality of many apprenticeship schemes remains an issue, and it is in any event not clear that incentives of this kind are

efficient in view of the deadweight associated with providing a break to employers that would in any event have provided the training.

A particularly welcome innovation is the proposal for a loan scheme to finance taught postgraduate education. This will help end the current inequity that

has made tuition at this level affordable (more or less) only to those with private resources.

Overall, the Statement is one with much detail to be pored over, but lacking a clear vision of the route ahead. The cuts that remain to be made in public

spending are severe, and we still await information on where the axe is intended to fall.

Underemployment figures show labour market slack remains

25 November 2014

In recent months, we have published a regular series of data on underemployment in the UK - the Bell Blanchflower Index. These data have suggested that the

extent of underemployment rose markedly during the recession and has remained substantial since.

Now the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has released further information on the extent of underemployment. Around 10 per cent of workers employed in

the UK are working fewer hours than they want. This rises to about 20 per cent for those working in elementary occupations; there is also very significant

underemployment in the sales and customer service occupations and in caring, leisure and other services. For those who are underemployed, the average

extent of underemployment is staggering - some 11.3 hours per week. Clearly many workers who would like to work full-time have access only to part-time

work.

Underemployment is not a phenomenon confined to employees - self-employed workers may also be able to work fewer hours than they would like. The extent of

underemployment amongst this group increased particularly sharply with the recession. While, at the beginning of the last decade, underemployment amongst

the self-employed was around 2 percentage points lower than that amongst employees, the two groups now have virtually identical rates of underemployment.

This reinforces the view that much of the growth in self-employment since the recession has been linked to increasing insecurity in the labour market, the

position of many of the new self-employed being somewhat tenuous.

There is relatively little regional variation in the incidence of underemployment. It is highest in the North East, at 11.5%, and lowest in the East of

England, at 9.2%.

The ONS data also provide information about overemployment - people who would like to work fewer hours than they do. Around 10 per cent of workers fall

into this category, with concentrations in managerial and professional occupations. Health professionals, senior businesspersons (such as CEOs), and senior

officers in protective services (including defence) are particularly affected.

The net level of underemployment (that is, underemployment minus overemployment) amounts to around 900,000 hours per week. This is tantamount to about one

percentage point extra on the unemployment rate. While this figure is somewhat lower than the Bell Blanchflower estimate (largely because ONS use a more

restrictive definition of underemployment), it confirms what we have known for some time: the unemployment rate is no longer a sufficient measure of labour

market slack, and there remains scope for the labour market to improve further without generating significant wage pressure.

The minimum wage and young workers

19 November 2014

New data have been published today on the incidence of low pay. The figures come from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings and refer to April of each

year. Four distinct levels of the national minmum wage are relevant: apprentices in their first year and those aged 16-18 had a minimum wage of £2.68 per

hour; for other workers aged 16-17 the minimum wage was £3.72; workers aged 18-20 had a minimum wage of £5.03; and for all other workers the minimum wage

was £6.31.

The data show that the proportions of workers being paid less than the relevant minimum wage is markedly higher for young workers (aged 16-20) than is the

case for those aged 21 or more. For the latter group, well under 1% are paid below the minimum, but for younger employees the proportion is between 2.5 and

3%. In total, some 236000 workers receive a wage below the minimum, of whom 40000 are aged between 16 and 20.

This is, in part at least, due to the incidence of part-time employment amongst young workers, many of whom are still in education. Part-time employees are

much more likely than full-time workers to be paid low wages.

There is some regional variation in the incidence of very low pay - it is lowest in London, the South East and Scotland, and highest (by far) in Northern

Ireland. For the most part employers show a good understanding of the requirements associated with minimum wage legislation. It may be that there is work

still to be done in ensuring that they respond quickly enough to workers' changing minimum wage rates as the employees pass key birthdays or as they

graduate from apprentice status. It may also be that there is work still to be done in communicating effectively to employers their responsibilities to

younger workers.

More generally, there is a need for employers - and for society in general - to nurture younger workers, providing them with jobs that offer a genuine

career path with the promise of development and progression. At The Work Foundation we have undertaken a considerable amount of research in this area, a

useful summary of which appears here .

The latest quarterly data from the Bell-Blanchflower underemployment index

13 November 2014

The Labour Force Survey for the second quarter of 2014 is now available and allows computation of the Bell-Blanchflower underemployment measure for this

period. The time series for this variable, along with comparable data for the unemployment rate, is given in the table and graph below. In these data, the

underemployment rate is directly comparable to the unemployment rate – it adds to the unemployment rate the full-time equivalent net effect of hours that

workers would like to work but cannot. Since the second quarter of 2007, the underemployment rate has been persistently above the unemployment rate. The

gap widened quickly, and by the end of 2009 was almost 2 percentage points. It remained stubbornly at about this level – although it has reduced slightly

over recent quarters.

The gap between the underemployment rate and the unemployment rate is important. It represents slack that still exists in the labour market despite the

impression that might be given by a relatively low rate of unemployment. People who are in part-time work and who want to increase their hours of work can,

as the economy recovers, switch to full-time work. The most recent evidence suggests that an increasing proportion of the new jobs that are being created

are full-time. If this trend continues, then we should expect the gap between the unemployment rate and the underemployment rate to narrow, and the

unemployment rate will once again become an appropriate measure of labour market slack. In the meantime, there is still reason to suppose that unemployment

can fall further without adding substantively to wage pressure.

The overall economic situation is evolving quickly, but there would appear, on the basis of the evidence presented here, to be little reason to countenance

a tightening of policy over the coming few months. The international evidence suggests that the UK has been quite unusual in the extent of underemployment.

Data from Eurostat indicate that – aside from Spain, Cyprus and Ireland, the UK is the country with the highest incidence of part-time workers who are

underemployed. The reasons for this are as yet not well understood, but what is clear is that the old models in which the unemployment rate alone sufficed

as a measure of labour market tightness are no longer adequate.

November Director's Report

11 November 2014

Low pay is in the news. Between 2010 and 2013, the hourly pay of full-time men at the bottom decile of the wage distribution rose from £7.20 to £7.50 – an

increase of some 4.2%. The corresponding figures for women were £6.72 and £7.00 – also representing a 4.2% increase. But over the same period, prices rose

by more than 10%, implying a fall of around 6% in real pay.

In 2013, the Living Wage – which measures the wage deemed necessary for a full-time worker to cover the cost of necessities - was £7.45 per hour outside

London and £8.55 in the capital. It is clear that many full-time workers are being paid less than this basic level. This imposes strain on workers, their

families and communities. It imposes strain also on the public finances as welfare payments support those who could not otherwise make ends meet. It is

opportune therefore to ask what can be done to promote – and justify – higher pay.

Before answering that question, it is important to consider some of the factors that have brought us to the current situation. It is now almost 20 years

since Richard Freeman asked whether our wages are set in Beijing. His point was that global competition in traded goods and services puts downward pressure

on firms’ costs, including wages. This tendency has been exacerbated by the skill-biased nature of technical change, with technology becoming increasingly

complementary to the input of some workers but increasingly a substitute for tasks performed by others. The consequent ‘ hollowing-out’of the labour market

has since been well documented. Over the years since the Great Recession, labour productivity has stagnated . This reflects partly the mix of jobs

available – the productivity of some workers being constrained by the jobs they do – but it also reflects a marked decline in productivitywithin

occupations.

The Work Foundation’s recent report on low pay describes the problem in some detail, and makes recommendations for action by policy-makers and

practitioners. These include the development of new career ladders that are not locked into old patterns but that recognise the constraints and

opportunities offered by technological developments. They include also recommendations on the role that should be played by Local Enterprise Partnerships

and sector organisations in supporting business through times of rapid change in the labour market. Further recommendations concern the remit of the Low

Pay Commission and the role that should be played by the Living Wage in future policy.

It’s not enough though. More work is needed to support businesses and policy-makers in providing a framework that can support a sustained increase in

productivity and pay. At The Work Foundation, we will do our part by continuing to produce research in this area – indeed we are currently entering a new

phase of work. If you would like to know more about this, do please get in touch.

Will devolving powers to Manchester really stimulate economic development?

03 November 2014

The Chancellor of the Exchequer has announced that new powers are to be devolved to the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA). The GMCA will gain

powers in the areas of policing, planning, transport and housing, and will be required to introduce the post of a directly elected mayor.

These powers are modest and do not offer the promise of any real capability to stimulate economic development. If the north of England is to be able to

position itself as more power is devolved to Scotland and other regions, it will itself need further dicretionary powers.

But the absence of such powers in the current proposals might in fact be a blessing.

For while this move is being portrayed as progress in the development of the Northern Powerhouse, it is not at all clear that it represents a positive

development in that context. The Northern Powerhouse is intended to create a single urban area stretching across the Pennines, bringing in Leeds and

Sheffield as well as Manchester - and reaching out further in both directions along the M62 corridor. Creation of a nexus of political authority in

Manchester may well hinder economic integration of the north rather than aid it.

Northern cities face a drain of human capital to London and they lack the capital's levels of business investment. The disadvantage faced by the north thus

amounts to much more than the lack of a high speed rail link over the Pennines. Integration requires a unified political purpose that is not well served by

creating divisions now between Greater Manchester and weaker local authorities elsewhere.

Creating new jurisdications in a UK that is characterised by devolved government requires careful thought. It should not come about purely as a consequence

of 10 local authorities deciding to work together. Wider interests are at stake, and central government has a duty to take those fully into consideration.

Should Manchester be a metro in its own right? What then of the Northern Powerhouse? So should the metro include Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield? Maybe. But

what then of Newcastle? And what of the rural areas in between? These are questions worthy of debate. Computable general equilibrium models are used to

evaluate such issues elsewhere. Serious research is needed in the UK too.

Today's first step is not altogether promising.

October Director's blog

14 October 2014

The performance of the UK economy over the last year has been remarkable. Output has increased by over 3 per cent. The unemployment rate, which had

previously been stuck at just under 8 per cent for a long time, has fallen dramatically and now stands at 6 per cent. The benefits of this fall have been

felt by people across the country and in all demographic groups.

There nevertheless remains a curious sense of unease about the performance of the labour market. Productivity has continued to stagnate, and this has meant

that increases in wages have not been able to keep pace with price rises. People in work might wonder why they don't feel better off than a while back -

and the simple answer is: it's because they aren't.

Over the last few months, however, there has been a dramatic turnaround in the level ofbusiness investment. The latest figures suggest a year on year

increase of more than 10 per cent. This should mean that workers have better equipment with which to work. Whether or not they do, of course, depends on

what lies beneath the aggregate figures. But if they do, then we should, within the next year, start to see productivity grow once more. That would at last

bring about a renewed increase in real wages.

Increased investment should also serve to ease capacity constraints, hence allowing further growth. While a low unemployment rate might ordinarily indicate

that there are capacity constraints arising also from a limited workforce, that is unlikely to be the case at present. Underemployment - where many people

are working fewer hours than they would like - and a high incidence of (what appears to be involuntary) self-employment both suggest that there is room for

further growth in the number of hours worked. To be sure, in some sectors - particularly advanced manufacturing - there are emerging signs of skills

shortages and rising real wages, but this is very much the exception rather than the rule. There remains considerable slack in the labour market, and, this

being the case, there is no sign yet of inflationary pressure. A reasonable estimate of the ‘natural rate’ of unemployment on the basis of recent years’

data suggests that unemployment could fall to as low as, or even slightly below, 4 per cent before inflation kicks in.

The remarkable growth that we have seen in recent months should not, however, blind us to the fact that it is remarkable. Looking forward to 2015, it would

be surprising if output were to continue to grow at the present rate. Growth in our major export economies remains sluggish, and exchange rate movements

over the last year are not helpful. As the EEF has recently cautioned, the outlook for demand is less certain now than it has been for while. Indeed, the

latest data on industrial production suggests that – in the production industries – growth has stalled. The economy overall should continue to grow next

year, but at a slower pace than we have seen in recent months.

Migration and the labour market

30 September 2014

The CIPD has today (30 September 2014) published a landmark study on the growth of migration to the UK from other parts of the EU. Migration is an emotive

subject, and the report is likely to attract widespread attention. Based as it is on significant new research, it should serve to enrich the evidence base

upon which discussion takes place. It is therefore very welcome.

As a proportion of total employment, the number of non-UK born workers has risen steadily over time; now at around 15%, the percentage has doubled since

the late 1990s. Employment of non-UK born workers from the accession countries of eastern Europe shows a step change after 2004, when unrestricted

migration within the EU became possible for workers in these countries. These migrants have been disproportionately employed in low skill occupations - in

sharp contrast to migrants from western Europe and those from outside the EU that are subject to visa regulations. Hence they tend to be disproportionately

employed as cleaners, caretakers, catering assistants, and so on - typically jobs that are not directly customer facing and which do not demand strong

communication skills. But migrants from the EU are also disproportionately employed as accountants and IT specialists. So the picture is considerably more

nuanced than popular conceptions might suggest.

Many of the migrants from eastern Europe, in particular, are overqualified for the jobs that they are currently undertaking. Indeed, since 2007, most

migrants from these countries who have degrees have been employed in low skill work. There would appear to be significant scope for increasing productivity

within the UK economy simply by employing these migrants' skills to best advantage. It is important, however, to note that employers do not consider

migrants generally to be working below capacity within their current jobs. Facilitating job mobility amongst well qualified migrants thus offers the

promise of high returns.

Employers cite the main reasons for employing migrants to be availability, followed by their work ethic and the congruence of migrants' values with those

of the employing organisations. Some 26% of employers claim to have found difficulties in finding UK born workers to fill unskilled or semi-skilled jobs,

and 20% employ migrants because of the perception that they have a better work ethic than UK born workers. The attributes that employers particularly value

amongst migrants include their teamworking skills, their orientation to customer service, their conformity to what the organisation wants, and their

integrity.

While employers who employ migrant workers report a beneficial impact, those who do not employ migrants tend to report that they do not perceive a benefit.

This suggests that there are few spillovers. In particular, migration does not appear to be benefitting employers by pushing down the general level of

wages. Only 6% of employers claim that they would raise wages to fill posts were migrant workers not available.

Migration is not, in any large measure, displacing training. Employers who recruit migrant workers are more likely than other employers to be investing in

training and apprenticeships. To some extent, this results from a scale effect - larger employers are more likely to do employ migrants and more likely to

train.

There is a marked spatial difference in UK workers' attitudes to migrants - low skilled workers in London regard migrants more favourably than those

outside the capital. This may be related to the high stock of migrants in London - a case of familiarity breeding acceptance rather than contempt.

Meanwhile, there is concern that migrants who take on low skill work are competing with UK domiciled school leavers. This serves to focus attention on the

skills with which these school leavers are equipped. Over a third of 16 year old school leavers - and almost as many 17-18 year olds - are deemed to be

poorly or very poorly prepared for the world of work. Equipping them better is clearly a prerequisite for enabling them to compete effectively and secure

good jobs.

And this is the overall impression with which one is left after reading the report - migration is really a red herring. It is time for the debate to move

on to this: how can we best equip young people born and raised in the UK so that they can compete effectively in the labour market - without a need for

protectionism?

September Director's report

17 September 2014

As recently as two years ago, there were over a million young people, between the ages of 16 and 24, unemployed in the UK. The figure has fallen sharply as

the economy has recovered, and the latest figure is just under three quarters of a million. The problem of youth unemployment seems to be receding fast.

But the new generation of workers faces a labour market that is changing rapidly, one in which the sources of insecurity are many. Technological change is

leading to a redefinition of many jobs. Reports of robots stealing humans' employment are surely a case of sensationalism - after all, the humans are still

available to work. But the type of work that people are called upon to do is changing. Many observers have referred to a 'hollowing out' of the labour

market, or the development of an 'hourglass' labour market - one in which the demand for labour at the extremes of the skills distribution is buoyant, but

the demand for intermediate skills is stagnant.

Matching young people's skills and potential to the jobs that are available is made difficult when the distribution of these skills differs substantially

from the patterns of skills that are in demand. As the demand for skills evolves with the introduction of new technologies, so workers must be equipped to

complement these technologies to best effect. This means training and re-training through the life cycle - and a much more fluid relationship between

education, training and work than we have seen before. It also means that career structures within organisations need to be dismantled and redesigned so

that progression remains possible. Young people need to develop their abilities in ways that enable them to contribute their utmost, and they need to know

that they can be rewarded with careers, not just jobs.

The Work Foundation will be hosting fringe events at party conferences over the next month. These events, 'More than a job -creating career opportunities

for young people' will focus on the challenge of providing young people with careers that entail a process of skills development, productivity enhancement,

and progression. Put together, this amounts to a new covenant between society and our young people - one that protects them and nurtures their talents. If

we fail to achieve this, the long term outlook for our economy is one of stagnation, but if we succeed, the potential rewards are huge.

A recovery that is struggling to sustain itself

17 September 2014

Unemployment has continued to fall, with the rate now standing at 6.2% (compared with 6.4% in last month's statistics). The number of employees in

employment has risen by some 65000 over the last quarter. Almost half of this gain (some 30,000) is in part-time work, once again reinforcing concerns that

there remains a significant measure of underemployment. The numbers of part-time self-employed workers have also risen (by 17,000), but full-time

self-employment figures have fallen (by 13,000), emphasising the insecure nature of many of these jobs. Overall, while the continued fall in unemployment

is welcome, the impression given by these data is one of a recovery that is struggling to sustain itself.

At regional level, there have been marginal increases in the unemployment rate in the North East, the South West and in Wales. By some distance, this

leaves the North East (at 9.9%) the region with the highest unemployment rate.

Of those regions where the unemployment rate has fallen fastest, the fall has been especially pronounced in the North West, Yorkshire and Humberside, the

East Midlands, London and Scotland. The unemployment rate in Scotland, at 6%, is currently the lowest of any of the four home countries.

One reason why the rate at which unemployment might be slowing down is that it has fallen almost as far as it can go - in other words that capacity

constraints are starting to bite in the labour market. If that were the case, we would start to see skills shortages and consequently increasing earnings.

There have, to be sure, been some signs of this in some sectors, notably manufacturing, in recent months. But overall, the rate of growth of earnings

remains extremely muted. In July, the year on year growth in average weekly earnings amounted to just 0.7% - up from 0.6% the previous month but still a

long way short of the current rate of price inflation. Wage inflation remains relatively high in manufacturing (1.8%) though it is slowing. In

construction, wages rose by 4% year on year - and this sector will be an interesting one to watch over the coming months. But in services, which dominate

the UK economy, wage growth is still very sluggish indeed (0.3% overall), and wages are still falling in some sectors. While underemployment remains so

high, the evidence from earnings data is that we are still a long way short of capacity.

The resolution of the cost of living dilemma lies in boosting productivity. But this remains stubbornly sluggish. The large increase in business investment

over recent months should help restore productivity growth, so there is cause for some degree of optimism that real wage growth should reappear sometime in

the next year. But, as The Work Foundation's roundtable on productivity established, there are likely to be some deep-seated and long-lasting barriers to a

rapid recovery. Growth may continue, but it is likely to do so at a slower rate than in recent months, and it is clear the restoration of a fully normal

economy is going to be a long term project.

Education at a glance

09 September 2014

The OECD has published its annual review of education statistics, Education at a Glance. As ever, this provides a wealth of data that together contribute

to provide a fascinating insight into the world of education in developed countries.

The report raises concerns about changes in the extent of social mobility. Averaged across all countries in the report, upward mobility across generations

- measured by the proportion of a younger generation that is better educated than its forebears - is falling as new cohorts enter the labour market, and

downward mobility is increasing. The report describes this as a 'setback' though in truth it may just be an artefact of the data. At a time when a high

proportion of parents are well educated, it is naturally less possible for a high proportion of their children to be better educated than their parents.

Averaged across the countries in the sample, graduation from upper secondary level has continued to rise steadily over recent years, and has reached a high

of 84% in 2012. By way of contrast, the report finds that the graduation rate from tertiary education fell slightly in 2012; this result should however be

treated with considerable caution, since some countries (Luxembourg, Chile) with low rates entered the data only in 2012, while other data for this year

are not yet available for other countries (Australia, the UK) with high participation rates in higher education. Overall, the picture is one of continued

high and rising levels of enrolment in post-compulsory education.

This is unsurprising, since the incentives to participate in education remain very high. Averaging across the OECD countries, higher education graduates

earn around 60% more than upper secondary graduates - who in turn earn around a third more than lower secondary graduates. These proportions have remained

virtually unchanged over the last decade and a half at least. The distributions are somewhat more compressed in some northern European countries (notably

Sweden, Denmark and Estonia) but are remarkably consistent across the other countries in the data set.

While the concerns raised in the report about social mobility may overstate the extent to which younger generations are disadvantaging themselves by not

investing as much as their parents in education, the fact that education is a major driver of individual progress remains as true as ever.

Bridging the skills canyon

04 September 2014

Today (4th September) sees the launch of an important new report by the Centre for Cities and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. The report concerns the role

that cities need to play over the coming years in providing individuals with a route out of low paid employment and into more productive and remunerative

work.

The squeezed middle of the skill distribution has received considerable attention of late. There is much evidence, in the new report and elsewhere, to

suggest that the demand for intermediate skills is falling in relation to that for skills at the top and bottom ends of the distribution. This has often

been put down to the effects of new technology. Robots can undertake many of the tasks that have been performed by workers of intermediate skills,

heretofore. Moreover, new technology could replace some functions of highly skilled workers, taking over the role of diagnosis from medical practitioners,

for example.

Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne at Oxford University have gone so far as to suggest that around 50% of current jobs could vanish over the next 20

years as a consequence of computerisation. This has, understandably enough, led to some hysteria. But the reality is that jobs are each made up of a number

of tasks; it is the tasks, not the jobs themselves, that are taken over by technology. As workers find technological solutions to make their jobs easier,

the technology takes on some of the burden of their work, but the humans turn their efforts to other tasks. Jobs don't vanish. They morph. And, even if a

job currently undertaken by a human were to vanish, that human would still be available to do other jobs.

The squeezed middle is nevertheless a real phenomenon, and we do face the danger that some people might get locked into low productivity, low pay work, and

that they might be unable to traverse the canyon that is emerging between such jobs and the high quality jobs that are well remunerated. It is crucial to

remember at this point that it is the demand for skills that is bifurcating, not the supply. Workers are as able to make incremental improvements to their

skill sets as they ever were. The gap between the low paid jobs and the well paid jobs should not be harder for them to bridge simply because the canyon is

wider - many of those in low skill work have skills that exceed those required to perform their jobs, and it should in principle be possible for them to

upskill and make the jump to a better quality job. In a world populated by baristas and bankers, many of those in low productivity occupations already have

the ability and many of the skills needed to undertake higher productivity work. Identifying those who can and investing in them offers the prospect of

huge returns.

There is, however, a great difference between what should be possible and what actually happens. Ensuring that as many workers as possible are empowered to

make the most of their abilities is going to be more crucial than ever to economic development. The reward is that, in this new world, relatively small

investments in skill development can lead to substantial changes in the qualitative nature of the jobs that (at least some) workers can do. These

investments are critical to the growth of productivity. By ensuring that the investments are made, cities, regions and the national economy stand to gain

much in terms of output growth.

Cities have a key role to play, not least because the skill sets required within one urban area can differ substantially from that needed in another. Fully

taking advantage of opportunities to enhance productivity requires a local steer. Ensuring that human resource development meets industry needs calls for

training that is led by business. Cities, employers, education providers and central government all need to work together to face the new challenges. In

focusing on the role played by cities, the new report admirably draws a road map that will be useful in tackling the challenges that lie ahead.

August Director's Report

13 August 2014

Over the last 30 years, life expectancy at birth in the UK has been increasing by 2½ years per decade. A boy born now can expect to live to the age of 79,

while a girl can expect to live to the age of 83. Moreover, the increase in life expectancy that we have seen in recent decades isexpected to continue, so

children born in 2030 will expect to live even longer than those born now.

The ageing of the population has clear implications for those who are of working age. To support themselves in retirement, people will have to save more

while they are working and they will have to work longer. Both of these solutions present challenges to individuals, employers and government.

The savings rate in the UK has remained stubbornly low in comparison with international peers. Many large employers have put in place a variety of schemes

– including share ownership schemes – that encourage their workers to save. But there remains a dearth of serious research that can inform us about how the

detailed design of such schemes serves to incentivise different patterns of individual and aggregate saving. Insights from behavioural economics are likely

to be useful here; in particular, the idea that small policy changes can ‘nudge’ people into behaving in radically different ways. At the Work Foundation,

we are planning to investigate these issues using the Lancaster Experimental Economics Laboratory (LexEL), and our intent is that the insights we gain from

this will be profitably put into practice in many organisations.

Longer working lives also have implications for organisations as they manage their human resources. Succession management, promotion structures, human

resource development, an increased demand for flexible working, and the management of capacity issues are all likely to be challenged by increased

longevity. The scale of change is likely to be accelerated by the move from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions, not least because the impact

of economic turbulence on pension pots has been adverse, leading many workers to delay their retirement. The extent to which employers have prepared

themselves for what is likely to be a very rapid change is unclear. More clear is the fact that, in the new world, they will need to learn best practice

from each other very quickly.

At The Work Foundation, we are developing a new programme of research on ageing. This will cover all of the above issues and more. If you are interested in

finding out more about our plans, please get in touch with me – I shall be most keen to hear from you.

July's Director's report

15 July 2014

Unemployment scars people. This has been known for a long time, as has the importance of this for macroeconomic policy. If, as a result of a temporary

downturn in the economy, more people become unemployed, then, as the economy recovers, these people will find it relatively difficult to regain employment.

That means that what ought to be just temporary blips in unemployment develop a more permanent component. This phenomenon is known as hysteresis.

Two recent events at The Work Foundation have thrown the question of unemployment hysteresis into sharp relief. The first was the launch of our new report,

‘Sick of Being Unemployed’. This investigates the interplay between episodes of unemployment and ill health amongst men. Unemployment is a stressful

experience, and it is perhaps not surprising that it can lead to mental health problems. It can also, in consequence, result in behaviours that lead to

physical health problems – illnesses associated with smoking, drinking, or a sedentary lifestyle. Once their health suffers, the unemployed face a double

whammy – sick unemployed people are particularly unlikely to find their way back into work. So unemployment becomes hysteretic. Our report focuses on men,

because the evidence suggests that men are less capable than women in coping with unemployment – or at least they are less able to insulate health from

their labour market misfortunes. Managing the return to work for men who have suffered ill health is particularly important because work can contribute to

their recovery. At the macroeconomic level, if we can manage more people back into work, we can both raise output in the short term and break the vicious

circle that hysteresis represents.

Some (relatively) good news is that the Great Recession (in the UK) did not result in a massive increase in overall unemployment. While this is reassuring

to some extent, when we drill down to more detailed figures, there remains cause for concern about the longer term legacy of the experience of the last few

years. Youth unemployment did rise markedly during the recession, resulting in over a million young people being out of work. We have analysed this

phenomenon in some detail at The Work Foundation.

The second of our recent events was a seminar on young people and the recovery. This included the presentation of a paper by Mark Bryan and Alberto Tumino

which documents the long term scarring effects of unemployment on young people. Particularly striking is the fact that the scarring appears to be deeper if

young people first enter the labour market during times of recession.

Does this mean that the damage is already done? Have we lost a generation of young people? Not necessarily. But it does mean that that generation will need

unusual support to help them face the challenge of first entering employment and then living up to their full potential.Apprenticeships help – but they

need both to target the right people and to provide continuing support. Monitoring, and responding effectively to the needs of, those currently in their

early to mid-twenties will be a crucial investment. The penalty for getting it wrong is unfulfilled lives and a huge loss of potential output.

June Director's Report

10 June 2014

The European elections last month pushed to the fore questions about migration. These were reinforced on polling day by the release of the latest

statistics on immigration. These showed that the number of work-related visas issued in the last year has risen by some 10% - the bulk of this increase

being in the skilled (tier 2) category. In the year ending March 2014, the total number of work-related visas issued was a little over 156,000. The

government's target of reducing immigration to the tens of thousands appears to be slipping further away.

That might not be a bad thing. People migrate because they can benefit from doing so. To an approximation, workers get paid in line with their

productivity. If their productivity is greater in one place than in another - perhaps because the equipment they have to work with is better, or because

other resources are better, or because they are better managed - then the output of Earth Inc. rises, and we all benefit from that.

Of course, the world is not really quite so simple. Rapid movements of population bring about pressure points. Public services may be strained if the size

of a local population is rising rapidly, and (leaving the economics aside for a moment) people take time to adjust to new environments and new neighbours.

Leaving economics even further behind, people seem to believe that migration is bad for the labour market prospects of people who were born here; others

suggest that it is bad for the public finances. These notions have been comprehensively debunked by many studies - see for example an early Work Foundation

study on labour market effects, and the recent OECD report on the tax and benefit implications. Despite the evidence, these issues seem to remain a concern

for many people.

At least some of the above issues mean that there is a need for managing migration, and that is exactly what the government's points system aims to do. For

sure the system could benefit from some tweaks - it is not easy for smaller firms to navigate, and larger firms face challenges over its impact on

intra-company transfers. But the underlying premise of the system seems sound.

The points system does not, of course, cover migrants from the European Union. Neither do the figures on visas reported above. While the policy position

with regard to European migrants stays as it is, policy concerning migration from outside the EU has to flex to accommodate changes in flows of European

migrants. This imposes an added layer of complexity.

Debates about migration tend to polarise, with one side arguing for open borders and the other for tight controls. This does not seem to be a very grown up

way of going about things. We know that there are benefits to migration, and presumably these decrease (at the margin) as migration increases. We know

there are, in the short term at least, costs. So it should be possible to inform the debate by forming an evidence-based view about the optimal rate of

migration.

Policy-makers who wish to show some leadership on this issue might want to consider developing proposals that are based on evidence. They would then likely

face the task of educating the electorate. But the benefits attached to getting this right - something that is unlikely to happen by accident - could be

considerable.

The productivity puzzle - real or imagined?

28 May 2014

The economic history of recent years has been quite remarkable in many dimensions. One of the most notable features has been the sharp decline and

subsequent stagnation of labour productivity. Between 2007 and 2009, output per worker fell by over 5%. Over the subsequent four years, it rose by just 1%.

Since, owing to advances in technology, productivity usually grows year on year, the full effect of this is that productivity is now almost 20% below the

long run trend.

These statistics make the recent recession very different from many other recessions, particularly those of the 1980s and 1990s, after which productivity

recovered quite quickly. The initial decline in productivity is likely the result of a fall in demand; but one would normally expect firms to adjust their

labour input in line with this fall, thereby raising productivity, quite quickly. The prolonged fall in productivity is thus something of a puzzle. It is

not easy to imagine why we should have stopped being as good at doing things as we once were.

This productivity puzzle was the theme of a recent roundtable held at The Work Foundation. The context was set in presentations by Jonathan Haskel and

Charles Levy, with subsequent discussion involving representatives from the Treasury, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, the Office of

National Statistics, the Bank of England, and several other key agencies. While it is fair to say that (unsurprisingly enough) the roundtable did not solve

the puzzle, it succeeded in identifying several issues that are likely to be key to a solution, and also identified a promising and important agenda for

further research.

Several partial candidate explanations for the apparent slowdown in productivity were identified. Amongst these were:

• Changes in the composition of industry, notably the decline of capital intensive, high productivity, extractive industries such as oil. This may be a

partial explanation, but we know that productivity has declined within a wide range of sectors, not just in some industries.

• A decline in successful innovation, particularly in industries such as pharmaceuticals. This may contribute to falling productivity in some industries,

but it cannot explain the drop in productivity in industries that are less sensitive to innovation.

• Change in the composition of investment, with much investment now taking the form of R&D, design, brand management, reputation, and software

development. Over the last 20 years, such ‘intangibles’ have come to represent a far greater proportion than before of the economy’s investment – up from

under 10% to some 35%. When firms invest in intangibles, they seem to be spending resource on workers’ pay without getting a return – the intangibles are

not (by and large) treated as an investment in the national accounts, and so national output is mismeasured. This would suggest that GDP is, in reality,

higher than official figures suggest, and that productivity has not really fallen (or at least not by as much as the published data would lead us to

believe). However, investment represents a relatively small portion of GDP, and the increase in (unmeasured) investment would need to be far larger than is

currently the case if it were to explain more than a small part of the apparent decline in productivity.

• A change in the capital:labour ratio brought about by lower real wages. As real wages fell during the recession, firms may have substituted labour for

capital, with the hiring of lower productivity workers becoming increasingly worthwhile. Certainly, investment in physical capital has fallen and has

failed (so far) to recover – though many observers expect a marked bounce-back this year. To the extent that this has led to a deterioration of the toolkit

with which workers can use to undertake their jobs, one would expect it to lead to declining productivity. But whether the fall in the relative price of

labour has been sufficient of a trigger to bring this about is moot – especially given that a change in investment needs to be sustained over several years