The Strategy places considerable emphasis on ‘people’, and stresses the need ‘to create good jobs and greater earning power for all’. The commitment is that ‘as the economy adapts, we want everyone to access and enjoy good work’. Within government, the Business Secretary is to take on responsibility for the delivering quality jobs. Building on the Taylor Report, he will develop ‘a set of measures against which to assess job quality and success’ – including: ‘overall worker satisfaction; good pay; participation and progression; wellbeing; safety and security; and voice and autonomy’. Some aspects of good work, as defined in the literature, are notable in that they do not appear in this list – notably flexibility and worker co-determination. Sector Deals are proposed as one mechanism whereby job quality can be enhanced; there will need to be others.

While employment in the UK has recovered well from the Great Financial Crash, it is widely recognised that the economy suffers a serious problem of mismatch in the labour market. The Industrial Strategy seeks to address one aspect of this problem – an absolute shortfall of certain skills. In particular, it identifies gaps in skills in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and inequalities in educational achievement. The proposals in the Strategy to address these issues build upon innovations introduced in the last two Budgets – specifically in the provision of Technical level qualifications, apprenticeships, investment in mathematics education, and lifelong learning. The Strategy leaves another aspect untouched, however. Overeducation – or, rather, the allocation of well educated workers into jobs where they are less productive than they might otherwise be – has become an increasingly prominent issue. A part of any successful industrial strategy should therefore be to investigate how the operation of the labour market could be improved so that people can most effectively use the skills they already have.

The Strategy aims to tackle regional disparities in skills by devolving responsibility and budgets to mayoral areas. This is welcome, as local conditions are best understood by people working on the ground. More generally, the migration of highly skilled young workers to London is leading to coincident overheating in the capital and stalled recovery elsewhere. Investments made as part of the Industrial Strategy all have a spatial dimension, and active government support for initiatives ought explicitly to be conditional on promoting and maintaining regional balance; the need is for something with considerably more teeth than the regional mission of the British Business Bank heralded by the Strategy document. The Northern Powerhouse and Midlands Engine may be key to this – though it is critical that these initiatives should work together and not mutually frustrate each other. (If everywhere is a powerhouse, nowhere is a powerhouse – and there is a legitimate fear that regional politics may already have kiboshed George Osborne’s great idea.)

The UK has long lagged behind major competitor countries in its R&D spending, with combined public and private spending amounting to 1.7% of GDP. This compares with 2.8% in the US and 2.9% in Germany. The Strategy sets the goal of raising the proportion in the UK to 2.4% by 2027. This medium term goal appears modest, and indeed the Strategy itself sets an aspiration for a longer term target of 3%.

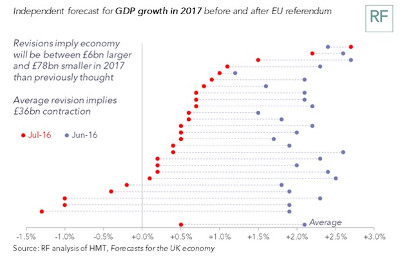

Overall, then, there is much to welcome in the Strategy. Productivity has been an issue in the UK economy for many years, and it is good to see government make explicit its responsibilities as an agent that can set the right environmental conditions for business to innovate. It is however a pity that the positive aspects of the Strategy are at odds with other relevant developments in the policy domain. The word Brexit does not appear in the document at all, and the only serious discussion of its implications for the substance of the Industrial Strategy is in a brief paragraph on the penultimate page. That aside, there is one page (with a lot of white space) that deals with migration – in a notably coy manner. The sad reality is that Brexit will take with one hand what the Industrial Strategy gives with the other.